Above is an example of bad editing!

Editing Part 2

What is the opposite of continuity editing?

Discontinuity editing

This means breaking the continuity editing rules. A lack of continuity in film. Certain techniques can be employed by the filmmaker to disrupt the flow of narrative events; rather than concealing the editing and stitching the audience in to the narrative, you can put the editing technique at the forefront. Look at some of these examples:

Can be done by employing the following techniques:

· Jump cuts

· Freeze frames

· Non-diegetic inserts (Natural Born Killers)

· Split screen (Show Timecode…)

What is the 30 degree rule?

The 30 degree rule ensures that camera shots are suitable for continuity.

If there is one character on screen and the shots change, to ensure continuity the 30 degree rule must be adhered to. The rule can be applied in two ways.

1. The camera moves directly towards character with no change in angle (this ensures that there’s no dramatic shift in space)

2. Angle changes between shot, change must be more than 30 degrees, creating a significantly different angle on the character. Making clear change in cameras relationship to background.

*If a second shot of a character is included where the shot angle doesn’t change, a jarring, jump cut effect will be seen.

Here is a useful video that demonstrates the rule: http://en.elephorm.com/camera-shooting-techniques-training/shot-types.html?autoPlay=true#video

Use of jump cuts – what happens when you break the 30 degree rule!

A jump cut is an edit the audience notices. Usually two shots edited together are not different enough from each other for a viewer to see the difference. However a jump cut is a cut between two very different shots.Normally, editors try to avoid jump cuts: but not always. In some filmmaking, such as the French New Wave of the 1950s, jump cuts have become a sign of the director’s artistic intentions. Other filmmakers use the jump cut to suggest a character’s state of mind. In Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, USA, 1990) and Summer of Sam (Spike Lee, USA, 1999), there are sequences in which a character’s drug-induced confusion is communicated through this technique.

A nice sequence of jump cuts occurs in Ocean’s Eleven (Steven Soderbergh, USA, 2001) when Linus (Matt Damon) is waiting inside the van. These cuts jump for two reasons. The 30° rule is broken, and Linus moves position each time. Consequently, an impression is given that a lot of time has passed between one cut and the next. Meanwhile, the sound of two other characters talking in the background is continuous, showing that there has been no ellipsis. The idea is to show that, for Linus, perceptual time is passing very slowly.

Montage

General Montage definition:

The type of montage in film we are used to seeing is ‘Hollywood montage’ like this example here:

Montage has different meanings. It was developed in the 1920s by Russian filmmakers (soviet montage). This term means editing in French and Russian. If you used montage in the traditional Hollywood way like above it shows images not always from same time and place but linked together and related so audience can understand.

In soviet montage editing it was used differently. This editing uses shots out of spatial or temporal order. In Battleship Potemkin (dir. Eisenstein,1925) montage is through quick cuts, shifts in screen direction, rapid moves between shots, cutting in on action, crosses in screen in various direction, repeated action, not all action is shown, drastically moving between camera positions; accentuating the feeling that violence is being perpetrated on a large group of people; but affecting individuals.

The Kuleshov Experiment

The Kuleshov Effect is a well-documented concept in film-making, discovered by Soviet film editor Lev Kuleshov in the 1920s.

Kuleshov put a film together, showing the expression of an actor, edited together with a plate of soup, a dead woman, and a woman on a recliner. Audiences praised the subtle acting, showing an almost imperceptible expression of hunger, grief, or lust in turn. The reality, of course, is that the same clip of the actor’s face was re-used, and the effect is created entirely by its superimposition with other images.

More generally, the Kuleshov Effect is the basis of Soviet montage cinema, and is used in many many films since. The idea is that, by editing different things together, it is possible to create meanings that didn’t exist in either of the images put together – constructing ‘sentences’ and ‘texts’ out of film. NEW MEANINGS are created.

A more updated example of this is in The Godfather (dir. Coppola, 1972)

In a famous sequence from the latter film, shots of Michael attending his son’s

baptism are intercut with the brutal killings of his rivals. Rather than

stressing the temporal simultaneity of the events (it is highly unlikely that

all of the New York Mafia heads can be caught off guard at exactly the same

time!), the montage suggests Michael’s dual nature and committement to both his

“families”, as well as his ability to gain acceptance into both on their own

terms — through religion and violence.

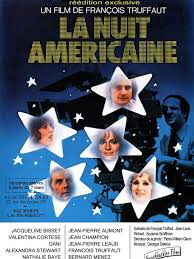

First Key Film Screening: La Nuit Americaine (dir. Truffaut, 1973).

Francois Truffaut is an important figure in film history. He was part of the French New Wave film movement. See info below.

The French New Wave Era

The French New Wave of the late 1950s, one of the key movements of post-war European filmmaking, forever altered long-established notions of cinema style, themes, narrative and audience. The New Wave (or Nouvelle Vague) showed the vibrant realism of Paris’ streets and its inhabitants at a time when many Hollywood films were still formulaic and studiobound.

A Hollywood film of the time would more than likely have included a linear narrative and uncomplicated shots and edits (such as a typical shot-reverse-shot); a film from the New Wave, however, would astonish you with extended shots, handheld footage, naturalistic performances, on-location shooting, whip-pans, socio-political commentary and ambiguous or unresolved endings. Today, its impact can still be felt in the work of many contemporary directors including Martin Scorsese, Bernardo Bertolucci and Quentin Tarantino.

So, why all the fuss? This quote from a 1961 French arts television documentary sums up the aims and ideals of the French New Wave perfectly: ‘Today’s young filmmakers are trying to make a different type of film and put an end to boring films. They deal with today’s problems, not those of the past. Their style is fresh and shocking, doing away with the dull and outdated. But what is all this commotion… What is it all about? The cinema. Who is it about? About the young cinema’

The French New Wave was born out of the dissatisfaction that many young filmmakers and critics felt towards the existing, outmoded, French cinema of the time. While cinema was the most popular entertainment option in France in the 1950s (it was, after all, not long after the war and television had yet to fully impact upon society there), serious art critics found the films on offer to be unchallenging, stolid and without vision. Critics of the existing order, including Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, believed an auteur cinema, in which the director’s vision was paramount and personal, should be developed. They wanted to make films in which social and political issues could be explored – films that felt ‘raw’ and new. Taking matters into their own hands (and a dash of inspiration from the Italian Neo-Realist movement), Truffaut, Godard and several others set about changing cinema forever. The New Wave was born.

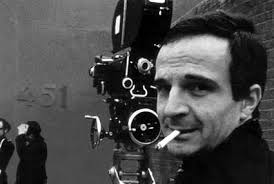

Francois Truffaut

It was the cinema that offered him the greatest escape from an unsatisfying home life. His obsession began at eight years old when he saw his first movie, Abel Gance’s Paradis perdu. As he got older he truanted frequently, sneaking into theatres because he didn’t have enough money for admission. The cinema became both a refuge and an alternative schoolroom. At the age of fourteen, after being excluded from school, he decided to be self taught. Among his academic “goals” were to watch three movies a day and read three books a week.

Read more on the director here: http://sensesofcinema.com/2003/great-directors/truffaut/

Have ready for next week a screening report on the film.